At the risk of sounding like a broken record, 2025 was, for the most part, a dark and dismal time. I realize I’ve said essentially the same thing for the last handful of years, but it’s starting to feel as if life is going, “Oh, I’m sorry—you thought that was bad? Hang on a second,” before proceeding to pile it on. It’s exhausting, frankly. I am exhausted.

But that’s so often the nature of life, isn’t it? A series of painful trials that we must endure in order to reach those agonizingly brief moments of respite and grace that remind us it’s all worth weathering in the end.

It was a dark year. I suppose my reading reflected a lot of that, intentionally or not. There is a lot of darkness in these pages—but, crucially, there is a hell of a lot of light, too.

These were the brief moments of respite and grace that made up my year:

LOVE AND LET DIE: JAMES BOND, THE BEATLES, AND THE BRITISH PSYCHE by John Higgs

There’s little I love more than unconventional nonfiction books that take vastly different subjects and manage to find the myriad of ways in which they not only connect, but are, actually, pretty much inextricable from one another. This book is the perfect exemplification of that conceit, and I enjoyed every page of it.

The central thesis of this volume (Bond = Death, Beatles = Love) is absolutely delicious, which is why I all but devoured it in just a couple of days. A perfect piece of pop punditry.

WITH A MIND TO KILL by Anthony Horowitz

Speaking of Bond, James Bond.

All due respect to Ian Fleming, but Anthony Horowitz may just be my favorite Bond writer. The man just exudes thrillers. Each of his 007 novels is better than the last, and it’s only appropriate that this, his last bow, turned out to be the most mature and layered of the lot. A magnificent end to a magnificent trilogy, and a fitting tribute to one of the most iconic characters in all of fiction.

THE HUMAN BULLET by Benjamin Percy

Benjamin Percy writes pitch-perfect pulp prose in the same vein as Ian Fleming and Richard Stark and his writing is among my favorite discoveries of the year.

HEAT 2 by Michael Mann, Meg Gardiner

The best movie I read all year. And I mean that in the most positive way possible. This was more cinematic and more thrilling than any film I managed to see this year. The raddest of stuff.

Y2K: HOW THE 2000S BECAME EVERYTHING by Colette Shade

All our shared millennial anger and resentment distilled into a short, eminently readable volume. I initially went into this for the vibes and nostalgia, but came out appreciative of its surprisingly nuanced takes on the politics of the era that, for better or worse, influenced, well, everything.

The new millennium vibes are still very much present, though. Recommend reading this while Moby’s “Porcelain” plays on a loop in the background.

SONGS FOR GHOSTS by Clara Kumagai

This was just straight-up gorgeous and I sobbed through pretty much the last hundred pages of it. One of my first starred reviews for Booklist.

THE TALENTED MR. RIPLEY by Patricia Highsmith

Tom Ripley is a fascinating, anxious little weirdo and I absolutely loved reading about him. Honestly surprised it took me so long to finally pick this up because it was so up my alley. Highsmith’s writing is flawless and impeccable, and I can’t wait to read more of her work. Heat 2 may be the most fun thing I read all year, but this was the best.

BENT HEAVENS by Daniel Kraus

A brutal, horrifying, genuinely unsettling story about the terrible lengths people will go to vilify what they don’t understand. This went nowhere I expected, and it is all the better for it. The best thing I picked up this Halloween season.

NO COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN by Cormac McCarthy

This is, of course, a famously bleak-as-hell narrative—though not without its charm. I actually found it quite funny at times. At others, profound. At others still, deeply disturbing. A very human, very haunting story. It’s haunting this human still. My first McCarthy. Probably not the last.

THE LAST DEVIL TO DIE by Richard Osman

Initially, I found the plot too meandering and all over the place, and it was on track to becoming my least favorite Murder Club mystery. But then we got to the halfway point—the literal heart of the story—and I could not stop bawling for the next handful of chapters, so obviously I ended up loving it.

Again, just some of the most beautiful characters I’ve ever had the pleasure of encountering. What a gift they are. What a gift they’ve been.

HONORABLE MENTIONS

BROKEN DOLLS by Ally Malinenko

Another Booklist highlight. Will always be fond of properly creepy children’s horror, particularly when it refuses to talk down to its young audience. Great stuff.

MYSTERY JAMES DIGS HER OWN GRAVE by Ally Russell

Case in point! My friend Ally remains unstoppable. I am, of course, grossly biased, but genuinely one of my favorite writers.

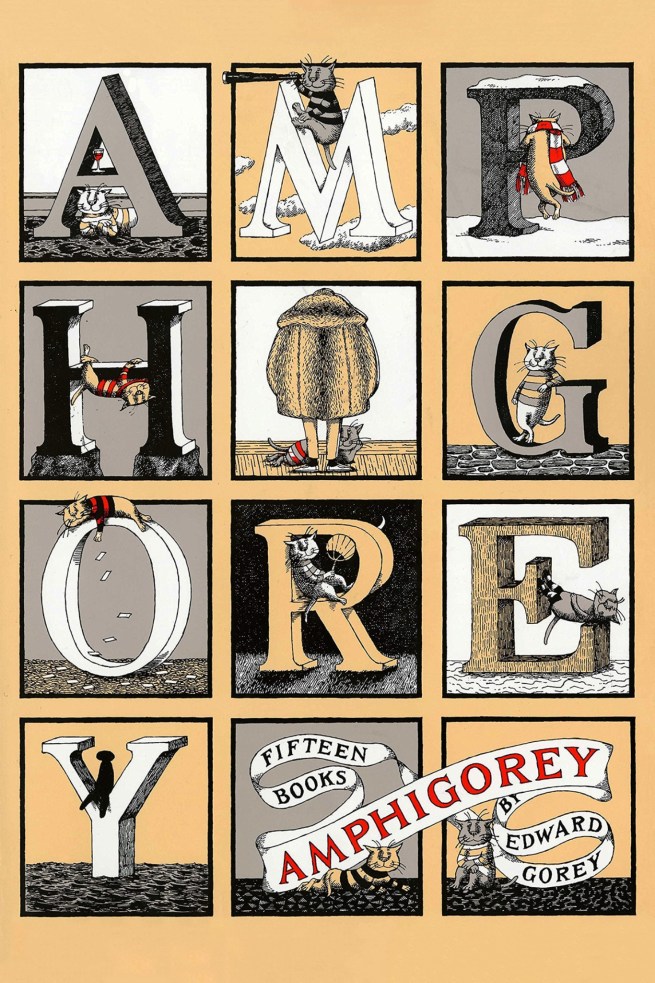

AMPHIGOREY ALSO by Edward Gorey

Delightful, needless to say. We adore Edward Gorey in this house.

YOU ARE NOW OLD ENOUGH TO HEAR THIS by Aaron Starmer

Yet another Booklist highlight. Weird and wild and wonderfully old-school. I enjoyed this middle grade throwback enormously.

SNOWED IN by Catherine Walsh

I read a handful of Christmassy romance books this holiday season and this one was my favorite. My mother has her hokey Hallmark movies and I have my corny Christmas rom-com books.

Here’s hoping there’s a lot more light in the coming year. I’ll be watching for it.

See you on the other side.